The delicate balance between user convenience and digital security has reached a breaking point for a significant portion of the OnePlus community. In recent weeks, a surge of reports has emerged from users of OnePlus devices—ranging from flagship models to the mid-range Nord series—who find themselves abruptly locked out of their financial lives. The culprit is not a malicious virus or a botched firmware update in the traditional sense, but rather a conflict between the sophisticated security protocols of modern banking applications and a native OnePlus system service titled “Frequently used info & passwords.” This internal accessibility tool, designed to streamline the user experience by managing credentials and autofill data, is increasingly being flagged by banking software as a high-risk "unknown screen reader," leading to the immediate termination of secure sessions and the blocking of critical One-Time Password (OTP) inputs.

The landscape of Android security has long been a battlefield. Traditionally, the primary hurdles for mobile banking enthusiasts were rooted in device modifications, such as unlocking the bootloader or obtaining root access. These actions trigger Google’s Play Integrity API (the successor to SafetyNet), which informs apps whether a device’s software environment is "clean" and untampered with. While the enthusiast community has often found workarounds for these integrity checks, the current crisis facing OnePlus users is far more insidious because it affects "stock" devices—phones that have never been modified and are running official OxygenOS or ColorOS builds.

The technical root of the issue lies in how banking applications interpret Android’s Accessibility Services. These services are powerful tools intended to assist users with disabilities, allowing apps to read screen content, simulate touches, and interact with other applications. However, because these capabilities are exactly what a banking trojan would need to perform an "overlay attack"—a method where a fake window is placed over a real banking app to steal credentials—financial institutions have become hyper-vigilant. Any accessibility service that the banking app does not recognize or deem "trusted" is treated as a potential threat. In the case of OnePlus, the "Frequently used info & passwords" service, which resides within the accessibility menu, is being categorized as a suspicious entity. When a user attempts to navigate a payment gateway or enter an OTP, the banking app detects this service active in the background, assumes the screen is being monitored by an unauthorized reader, and halts the transaction to prevent data exfiltration.

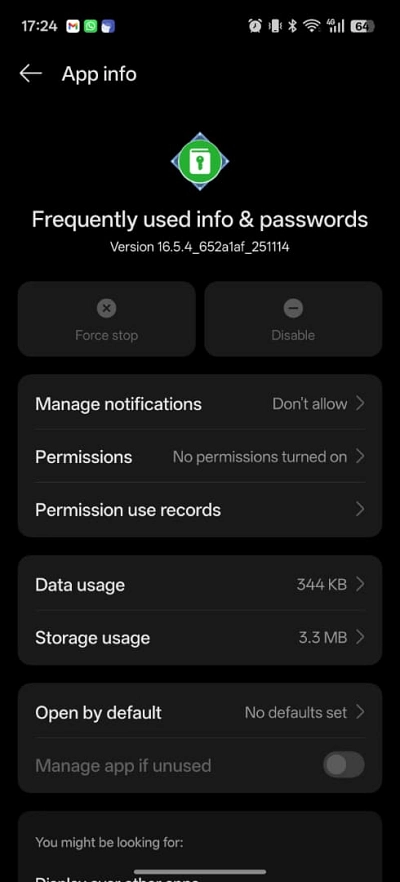

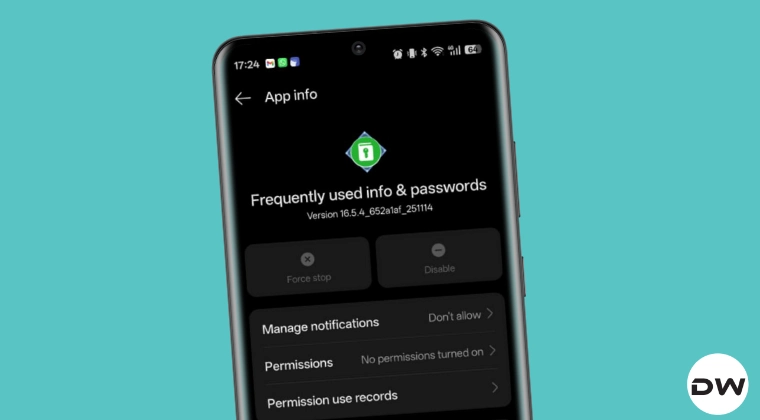

The frustration for the end-user is compounded by the persistent nature of this system component. Many affected individuals have attempted the logical first step: force-closing the app through the standard Android settings menu. Unfortunately, because "Frequently used info & passwords" is a core system-level service, it is programmed with high-priority persistence. Almost as soon as it is killed, the Android system restarts it to ensure that autofill functionalities remain available. This creates an exhausting loop where the user kills the service, opens their bank app, and finds the service has already resurrected itself, once again triggering the security block.

Located deep within the directory of Settings > Accessibility & Convenience > Accessibility > Downloaded Apps, the "Frequently used info & passwords" service is more than just a list of saved phrases. It acts as a bridge between the operating system’s credential vault and the active UI. By disabling or removing it, users are effectively performing a digital "trade-off." They regain the ability to use their banking apps and complete urgent financial transactions, but they lose the seamless convenience of automated password entry and the quick-access features that modern smartphones promise. For many, this is a regression to a more manual, cumbersome era of mobile usage, yet it is a necessary sacrifice when the alternative is being unable to pay bills or transfer funds.

For those pushed to the brink by these technical hurdles, two primary paths of intervention exist, both involving the use of the Android Debug Bridge (ADB). ADB is a versatile command-line tool that allows users to communicate with a device from a personal computer, providing a level of control over system packages that the standard touchscreen interface denies.

The first and most recommended approach is the temporary disabling of the service. This is a reversible "soft" fix that keeps the application files on the device but prevents the service from running or being detected by other apps. To execute this, a user must first enable "Developer Options" on their OnePlus device by tapping the Build Number seven times, then toggle on "USB Debugging." Once the device is connected to a computer with ADB installed, a specific command is issued to the package manager. Because OnePlus and its parent company, Oppo, have unified much of their software architecture, the specific package name can vary depending on the specific regional version of the software. Users typically have to target one of three package identities: com.oplus.passwordmanager, com.oneplus.passwordmanager, or com.oplus.autofill. By using the command adb shell pm disable-user --user 0 [package name], the service is neutralized, and banking apps generally return to full functionality immediately.

The second, more drastic measure is the complete uninstallation of the service for the current user. While this ensures the service will never interfere again, it is a path fraught with minor risks. If a user later decides they want their autofill features back, they cannot simply download the app from the Play Store, as it is a proprietary system component. Reinstalling it requires a specific ADB command—adb shell cmd package install-existing [package name]—to pull the original APK back from the device’s system partition. Journalistic observation suggests that for the average user, the "disable" method is far superior to the "uninstall" method, as it offers a safer fail-safe should the user realize they cannot live without the automated password manager.

The repercussions of these fixes are non-trivial. By silencing "Frequently used info & passwords," the user is essentially lobotomizing the device’s ability to recognize login fields across the OS. This means that every time a user needs to log into a social media account, a retail app, or a web portal, they will be forced to manually type their credentials or copy-paste them from a secondary password manager like Bitwarden or 1Password. While third-party managers often have their own accessibility services, they are frequently better recognized and "whitelisted" by banking apps than the native OnePlus implementation, which seems to be suffering from a lack of proper certification or metadata identification within the broader Android ecosystem.

This situation highlights a growing rift in the Android world. As Google pushes for tighter security through the Play Integrity API and as banks face increasing pressure to stop fraud, the "open" nature of Android is being squeezed. Manufacturers like OnePlus, who often implement custom "helper" apps to differentiate their software (OxygenOS/ColorOS) from "stock" Android, now find their custom code under the microscope. If a manufacturer does not coordinate closely with major financial software developers to ensure their system services are recognized as "safe," the end-user is the one who suffers.

The OnePlus community is currently looking toward future software patches for a permanent resolution. Ideally, OnePlus would update the "Frequently used info & passwords" service to comply with the latest security headers required by global banking standards, or they would work directly with major banking app developers to ensure the service is whitelisted. Until such an update arrives, the onus remains on the user to navigate the technical waters of ADB to keep their devices functional for daily financial tasks.

In conclusion, the "Frequently used info & passwords" issue is a stark reminder of the complexities of modern smartphone ownership. What was designed as a convenience feature has, through a lack of inter-industry synchronization, become a digital roadblock. For OnePlus owners, the choice is clear: prioritize the ease of autofill and risk financial lockout, or embrace the technical manual labor of ADB to ensure their banking apps remain operational. As the digital economy continues to shift almost entirely to mobile platforms, the pressure on OEMs to ensure their custom system services do not trigger false positives in security software will only intensify. For now, the command line remains the only reliable key to unlocking the full potential of a OnePlus device in a world of increasingly cautious banking security.